A new report from the Rappaport Institute of Greater Boston—“An economic analysis of the childcare and early education market in Massachusetts”— was released this week, and it calls for an increase in public funding.

“Given the overwhelming evidence that early childhood development affects later outcomes and that achievement gaps are already substantial by age five, it is puzzling that our society does not invest in early childhood education to at least the same extent as it invests in K-12 education,” the report says. “In Massachusetts, public support for early education amounts to approximately $3,700 per child, while public support for K-12 education amounts to approximately $20,000 per child.”

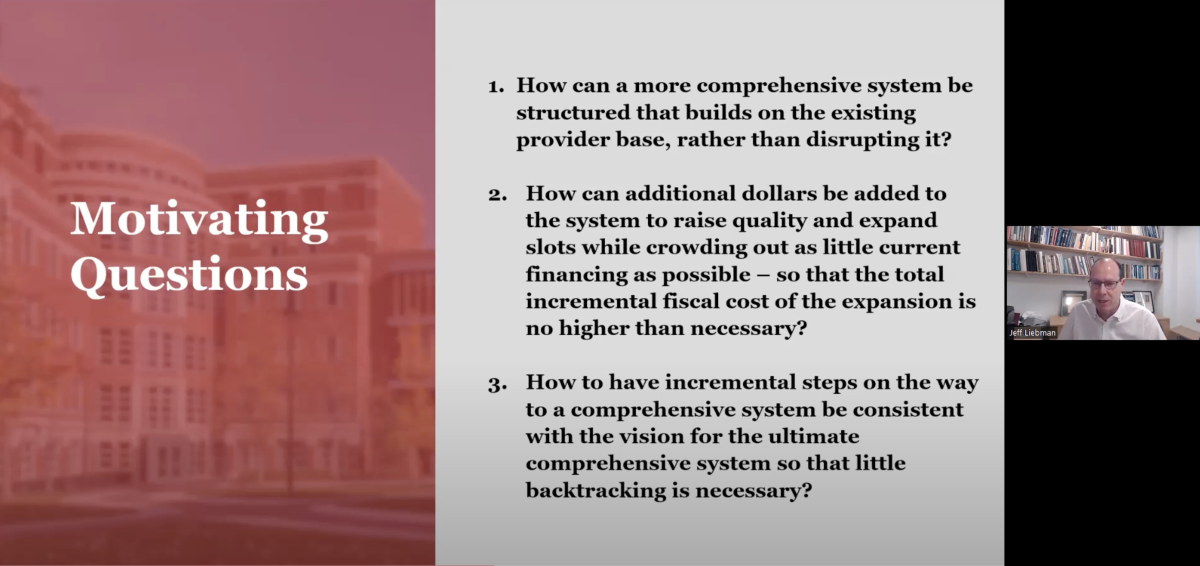

The report, which was written by Jeffrey Liebman, the director of the Rappaport Institute, part of Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, points to some of the key economic reasons that public funding of early childhood programs is so important.

Liebman spoke about the report

on The 9:30 Call.

Watch the recording here.

One reason public support is so important, the report explains, is because, “the market, without intervention, will not provide opportunity for all. Without help, lower-income families will not be able to afford care, and children in those families will not have the level of early education and care that society wants every child to have.”

And “the fact that high-quality care costs at least $20,000 to $30,000 annually, depending on the child’s age, implies that it is not even remotely possible that families with incomes of $30,000, $40,000, $50,000 or even higher are going to be able to afford care, and government subsidies will be needed in order to provide access for all.”

In addition, younger families often have fewer liquid assets. As the report notes, “the inability to borrow against future earnings means that even families who are not low income in a lifetime sense may end up spending too little on early education and care. Young children cannot go to the bank and take out a loan to finance their own high-quality early education, even if their future selves would happily repay the loan.”

The report also considers how increasing access to child care could enable more mothers to work and, in turn, boost their family incomes. And “if affordable child care were widely available, it might change fundamental decisions like career choices in a way that increases female employment and earnings. Finally, workers might not just be more likely to be in the labor force but also more productive if they and their colleagues were not stressed out about child care and missing work because of child care emergencies.”

To better target public dollars, there are a number of things Massachusetts could do, the report says, including:

- developing a better understanding of unmet demand for child care

- addressing the needs of middle income families who earn too much to be eligible for a child care subsidy and also lack the financial resources of wealthier families

- exploring the needs and preferences of parents whose children are infants. While their children are so young, these parents may prefer paid parental leave instead of infant child care. Or parents may want part-time or drop-in child care programs

- increasing the number of child care spots, especially in areas where demand exceeds supply

- boosting the quality of child care, which should include raising wages in order to retain staff, and

- reducing the cost of child care

Liebman presented the report at a Harvard University event that was attended by Amy O’Leary, Strategies’ executive director, and our fall intern Maria Suso. Suso says a key theme that was discussed is program quality: Liebman explained that without substantial public financing, the market will provide too few early education seats and those that do exist will, on average, be of lower than optimal quality. In the panel discussion that followed, Amy Kershaw, commissioner of the Department of Early Education and Care, was asked about her department’s strategy to improve program quality, and she said, “investment in our teachers is our quality strategy.”

Tom Weber, executive director of the MA Business Coalition for Early Childhood Education, was also in attendance, and shared his perspective on LinkedIn, writing the event was, “Possibly the most impactful analysis that I have heard this decade.”

As the report concludes, “Massachusetts has the opportunity to become the national leader in making high quality child care available to and affordable for all families. Getting there is going to require four steps: wage subsidies for early educators, investments in the early educator workforce, investments in capacity expansion, and carefully designed demand-side subsidies.”