Mention the achievement gap, and discussion often turns to a gap based on race. Yet the gap between white and black children in the United States has actually narrowed over the last several decades, The New York Times reports, while the gap based on income is widening.

“We have moved from a society in the 1950s and 1960s, in which race was more consequential than family income, to one today in which family income appears more determinative of educational success than race,†Sean F. Reardon, a Stanford University sociologist, tells the Times.

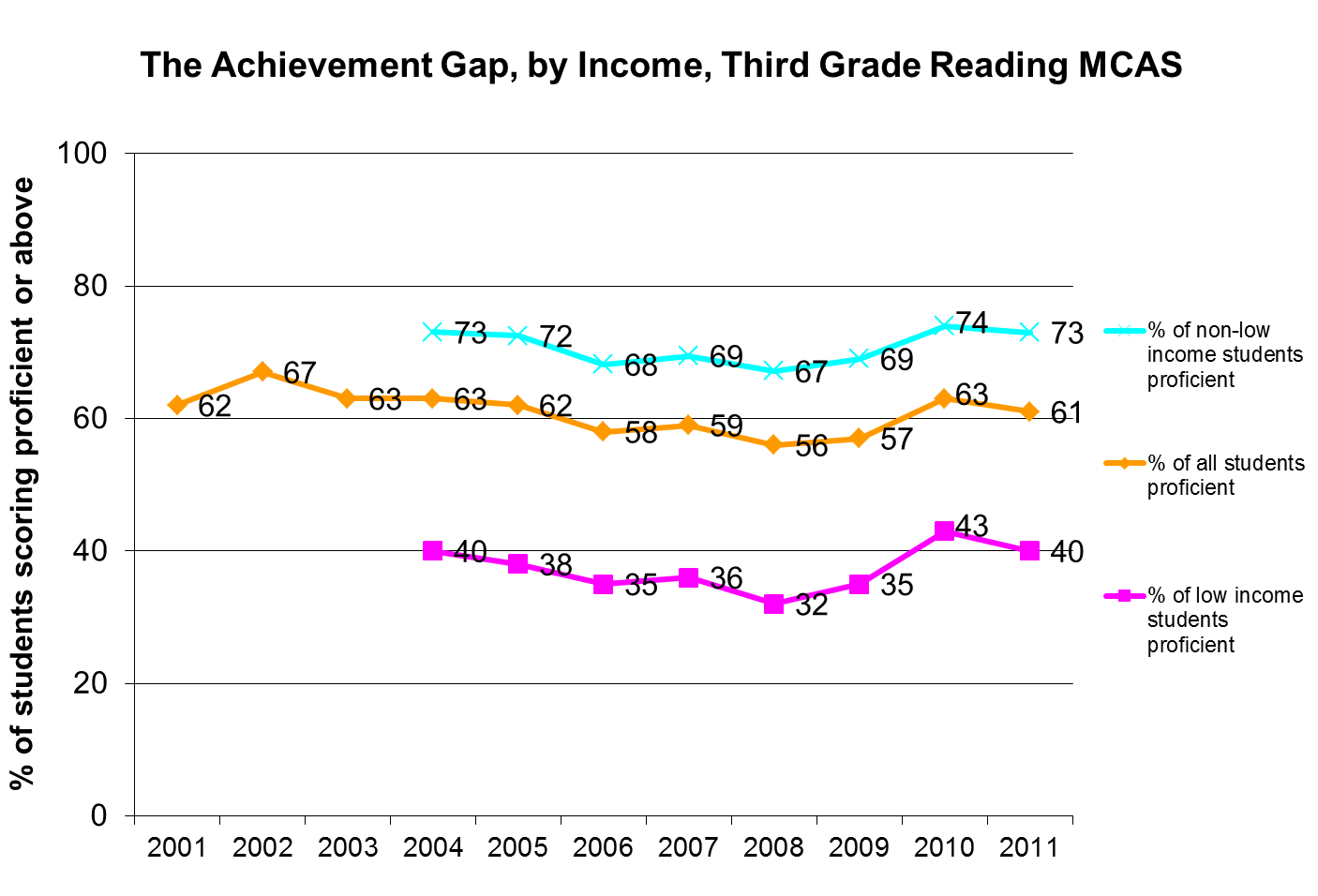

Reardon, in a recently published study, finds that the gap in standardized test scores between affluent and low-income students has grown about 40% since the 1960s. This is double the gaps between whites and blacks, the Times reports.

The Times also cites a University of Michigan study that finds the gap in college completion between affluent and poor students has jumped by roughly 50% since the late 1980s.

“The changes are tectonic,†the Times reports, “a result of social and economic processes unfolding over many decades. The data from most of these studies end in 2007 and 2008, before the recession’s full impact was felt. Researchers said that based on experiences during past recessions, the recent downturn was likely to have aggravated the trend.â€

Still another study, this one to be published this year in the Journal Demography, finds a growing gap in what parents spend on their children: “In 1972, Americans at the upper end of the income spectrum were spending five times as much per child as low-income families,†the Times reports. “By 2007 that gap had grown to nine to one; spending by upper-income families more than doubled, while spending by low-income families grew by 20 percent.†Co-author Frank Furstenberg, a sociologist at the University of Pennsylvania, tells the newspaper that “the pattern of privileged families today is intensive cultivation.â€

The Times story generated much comment.

“It may not simply be a matter of the rich getting richer, and the poor getting poorer — although that certainly is a part of it,†Jordan Weissman writes on The Atlantic blog. “The growing differences in student achievement don’t strictly mimic the way income inequality has skyrocketed since the middle of the 20th century. It’s actually worse than that. Today, there’s a much stronger connection between income and a child’s academic success than in the past. Having money is simply more important than it used to be when it comes to getting a good education. Or, as Reardon puts it, ‘A dollar of income…appears to buy more academic achievement than it did several decades ago.’

“Even more discouraging: The differences start early in a child’s life, then linger. Reardon notes another study which found that the rich-poor achievement gap between students is already big when they start kindergarten, and doesn’t change much over time. His own analysis shows a similar pattern.â€

On the Washington Post’s Answer Sheet blog, Century Foundation Senior Fellow Richard D. Kahlenberg notes “an array of strategies that can be highly effective in addressing the socioeconomic gaps in education.†High-quality pre-kindergarten is the first item on his list. “As  Century’s Greg Anrig has noted, there is a wide body of research suggesting that well-designed pre-k programs in places like Oklahoma have yielded significant achievement gains for students. Likewise, forthcoming Century Foundation research by Jeanne Reid of Teachers College, Columbia University, suggests that allowing children to attend socioeconomically integrated (as opposed to high-poverty) pre-k settings can have an important positive effect on learning.â€